This website is no longer updated, but we will keep it as an archive site.

Welcome to visit Satakielikuukausi website: www.satakielikuukausi.fi!

This website is no longer updated, but we will keep it as an archive site.

Welcome to visit Satakielikuukausi website: www.satakielikuukausi.fi!

In English below

Ahí estamos, frente a la estantería de la biblioteca del barrio, pensativos y alguna vez, un poco frustrados, preguntándonos: ¿por qué encuentro tan poca literatura infantil en lenguas minoritarias, como español? La respuesta a esta pregunta es válida para otras lenguas de herencia: porque la mayoría de los libros están en los depósitos de HelMet esperando que los reservemos y llevemos a casa.

¿Entonces, cómo hacer para que esos libros lleguen a casa? De esto trata este artículo. Compartimos nuestra experiencia con la colección de literatura infantil en español de HelMet, una colección con más de 1500 títulos. Creemos que este ejemplo puede ayudar a otras familias a buscar libros en sus propios idiomas.

La manera eficaz de acercarnos a las colecciones es usar el sitio web http://www.helmet.fi al que accedemos con el número de usuario de la biblioteca o nuestros hijos con el propio. Seguramente, si ya hemos usado el buscador del sitio, es sencillo ubicar esos libros que nos interesa; máxime si conocemos el nombre del autor o la editorial o el de una colección en particular o directamente el título del libro.

Sin embargo, si recién nos familiarizamos con la literatura para la infancia e intentamos buscar recomendaciones para la edad de nuestros hijos, sabemos por experiencia propia que no es sencillo. Por ejemplo, al explorar el sitio de HelMet (en finés, sueco o inglés) con la palabra clave “literatura infantil en español” o términos similares, nos lleva a un resultado increíble: (0) cero sugerencias. ¿Cómo es posible?

Hay que aclarar que, en general la búsqueda de literatura en lenguas minoritarias es un poco más compleja. A esto se suma que el personal de las bibliotecas no necesariamente está siempre preparado para asesorar a las familias acerca del inmenso mundo de la literatura infantil, y mucho menos aquella publicada en español, o cualquier otra lengua de herencia fuera de las nacionales.

Aun así, estas colecciones de literatura infantil en lenguas minoritarias existen. En el caso de la “Colección de literatura infantil en español” hay catalogados 1566 títulos para la infancia y 258 títulos más, que se recomiendan para jóvenes. Este número de títulos varía de mes a mes, esta era la situación la última vez que la consultamos: 20.2.2021. Mensualmente en el sitio de HelMet se publican las nuevas adquisiciones de todas las lenguas. Vale consultar y ver qué hay de nuevo aquí (helmet.fi).

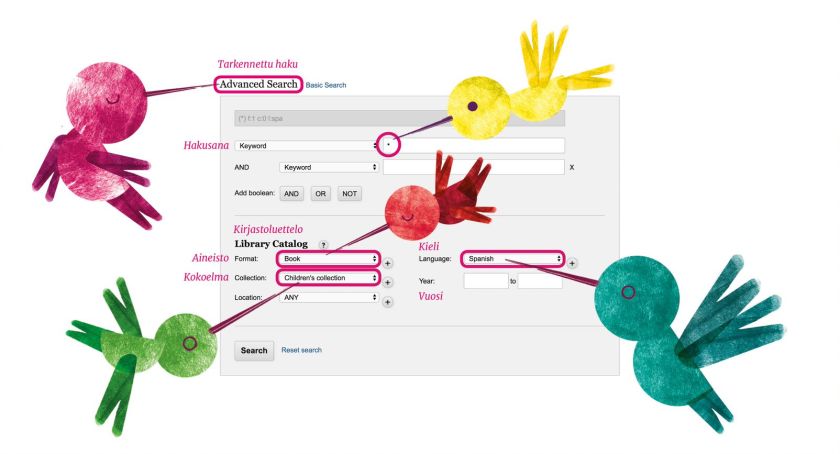

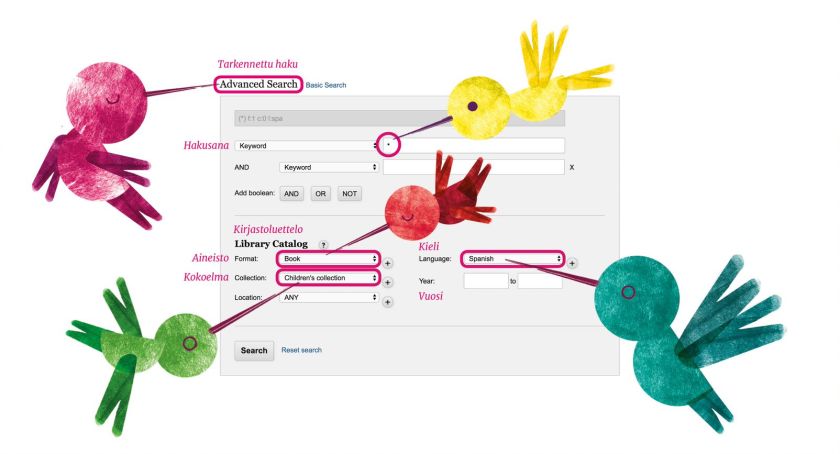

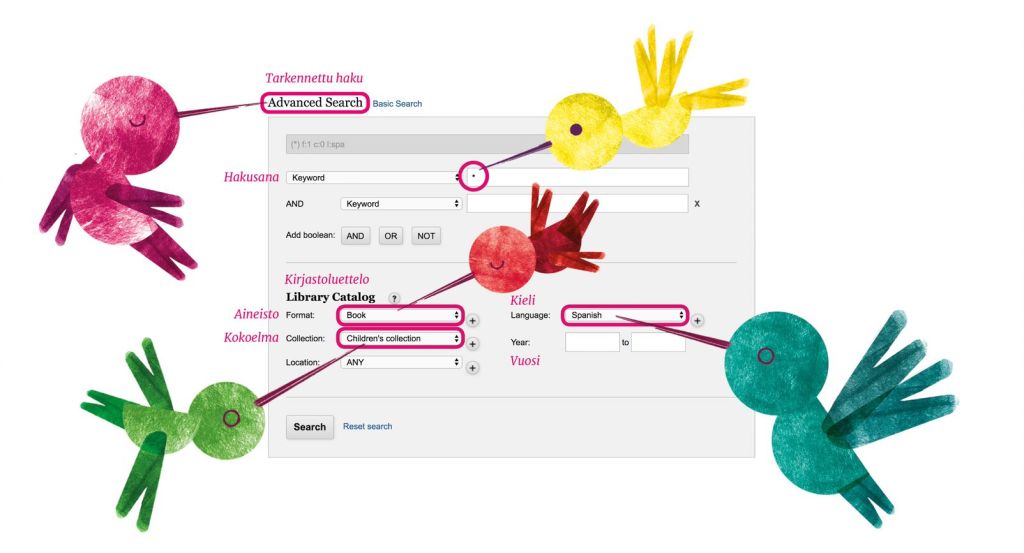

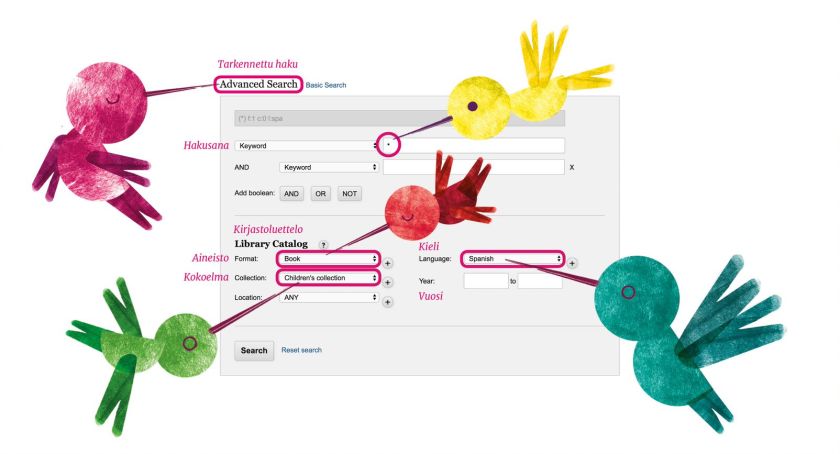

El camino para encontrar lo que estamos buscando, es familiarizarnos en el sitio web con la opción “búsqueda avanzada“. Cómo en la búsqueda del tesoro, necesitamos una clave. En este caso es un asterisco (*). Sí, abajo lo verán, en las orientaciones de los Kolibríes.

¡Atención con el Kolibrí amarillo! En Hakusana/keyword: vamos a colocar el asterisco (*). Después de completar la forma, como indicamos en la imagen y dar clic en buscar. Así, estaremos frente a toda la Colección de literatura infantil y juvenil en español disponible para llevar a casa.

Hay muchos libros por explorar, por eso al ingresar el catálogo sugerimos activar luego el casillero Genre, que está ubicado en el extremo inferior izquierdo. Este casillero nos ayudará, a organizar una búsqueda más precisa, por categorías, según la edad o intereses de nuestros futuros lectores. Estas categorías están sólo en finés. Seleccionamos y tradujimos algunas para ustedes:

Con estos recursos y los que vayamos explorando en las propias búsquedas, podremos animarnos a descubrir nuevos autores preferidos y a sacar muchos libros para leer en familia, para leer y entusiasmar a que nos lean. El sitio permite hacer listas de libros preferidos, para próximas lecturas, ordenarlos para que lleguen a la biblioteca más cercana a casa o al trabajo si resulta más sencillo. Y, sobre todo, esta colección permite que continuemos regalando palabras nuevas.

Entre estos libros infantiles existe una gran variedad. Hay libros para pre-lectores, libros para primeros lectores y para lectores avanzados. Para pre-lectores encontraremos libros bilingües, con pictogramas; también, libros que no son necesariamente literatura como los primeros libros para morder y ampliar el vocabulario, por ejemplo. Para los lectores, podremos llevar a casa novelas, clásicos, traducciones de autores reconocidos, libros de fantasía, aventuras, historietas, leyendas y cuentos populares, y muchos libros álbum. Incluso, hay varios libros de autores reconocidos de la literatura para adultos que pretendieron escribir para la infancia.

En el caso de esta colección, poco menos que la mitad de la colección son libros traducidos desde otros idiomas (545). Por ejemplo, algunos clásicos Tove Jansson (FI), Tuutikki Tolonen (FI), Timo Parvela (FI), Astrid Lindgren (SV) Sven Nordqvist (SV), Roald Dahl (UK), Mark Twain (EU), J. K. Rowling (UK), Lauren Child (UK), Cornelia Funke (DE), Hans Christian Andersen (DK), Eric Carle (EU). A esto se suman algunos libros de las grandes compañías audiovisuales.

Entre los 863 libros de autores e ilustradores hispanohablantes encontramos a: Isol Misenta (AR), Isidro Ferrer (ES), Paloma Valdivia (CL), Micaela Chirif (PE), Andrés Guerrero (ES), Graciela Montes (AR), Jordi Sierra i Fabra (ES), Luis Pescetti (AR), Ivar da Coll (CO), Elvira Lindo (ES), Manuel Marsol (ES), Jairo Aníbal Niño (CL), Emma Wolf (AR), María Cristina Ramos Guzmán (AR), María Teresa Andruetto (AR), María José Ferrada (CL), Pep Bruno (ES), Daniel Nesquens (ES) entre muchos más. ¡Les animamos a que los conozcan!

Lukupesä, “Nidos de lectura”, es el nuevo proyecto de Kulttuurikeskus Ninho para promoción de la literatura infantil e inclusión de las familias. El proyecto ofrece a madres, padres y otros interesados, un programa holístico para apoyar y desarrollar prácticas de lectura en español, portugués y en otras lenguas minoritarias. Nuestro Lukupesä está compuesto por una serie de sesiones de capacitación y talleres alrededor de este tema tan lindo como es la lectura en la primera infancia. A la vez, ayudará a las comunidades a aprovechar la infraestructura y los servicios existentes en la ciudad (ejem. bibliotecas y sus colecciones) no siempre tan accesibles desde la perspectiva de los inmigrantes.

Otro de los componentes de Lukupesä serán visitas guiadas por las colecciones de libros infantiles en HelMet por medio de sesiones cortas online en primavera y otoño donde esperamos buscar junto con otras familias libros infantiles para leer en casa. Las sesiones ofrecerán un punto de encuentro con información práctica sobre la mejor forma de encontrar buenos libros y autores según las edades y el interés de los niños.

Para más información les invitamos a estar atentos a nuestros medios sociales donde compartiremos estos eventos: Kolibrí Festivaali Facebook o Instagram: @kolibrifestivaali.

En nuestro caso, la literatura infantil en español y portugués, los libros de editoriales de América Latina representan una cantidad bastante menor en la colección de HELMET, respecto de las ediciones hechas en España o Portugal. Desde Kulttuurikeskus Ninho y con el apoyo de las embajadas de América Latina en Finlandia, estamos trabajando para ampliar la diversidad y la cantidad de libros para la infancia, juntos sumamos más de 100 títulos nuevos en los últimos años.

Recuerden mientras más libros llevemos a casa más esfuerzos dedicará HelMet a cuidar y hacer crecer estas colecciones. ¡Qué viva esta comunidad lectora en crecimiento!

¡Buena búsqueda y buenas lecturas!

There we stand, in front of the bookshelf at the local library, thinking and sometimes a little frustrated, wondering: Why do I find so little children’s literature in minority languages, such as Spanish? The answer to this question is valid for other heritage languages: because most of the books are in Helmet’s storage facilities waiting for us to reserve them and take them home.

So, how do you get these books home? That is what this article is about. We share our experience with HelMet’s collection of children’s literature in Spanish, a collection with more than 1,500 titles. We believe that this example can help other families to find books in their own languages.

The effective way to approach the collections is to use the website www.helmet.fi which we access with our library user ID or our children access with their own. Certainly, if we have already used the site’s search engine, it is easy to locate the books we are interested in; especially if we know the name of the author or the publisher or the name of a particular collection or the title of the book.

However, if we are new to children’s literature and try to find recommendations for our children’s age level, we know from our own experience that it is not easy. For example, browsing the HelMet site (in Finnish, Swedish or English) with the keyword “children’s literature in Spanish” or similar terms leads to an incredible result: (0) suggestions. How is it possible?

It should be noted that, in general, the search for literature in minority languages is a little more complex. In addition, library staff are not necessarily always prepared to advise families about the vast world of children’s literature, let alone that published in Spanish, or any other heritage language outside the national languages.

Even so, these collections of children’s literature in minority languages do exist. In the case of the “Collection of children’s literature in Spanish” there are 1566 titles catalogued for children and a further 258 titles recommended for young adults. This number of titles varies from month to month; this was the situation when last consulted: 20 February 2021. New acquisitions in all languages are published monthly on the HelMet website. It is worth checking and seeing what is new here (helmet.fi).

The way to find what you are looking for is to familiarise yourself on the website with the “advanced search” option. As in a treasure hunt, we need a key. In this case, an (*) asterisk. Yes, you will see it below, in the Kolibríes guide.

The Kolibríes indicate where and what to fill in to access the children’s literature collection in Spanish.

Pay attention to the yellow Kolibrí! In Hakusana/keyword: we will insert the asterisk (*). After filling in the form, press Search. Thus, we will see the entire Collection of children’s and young people’s literature in Spanish available to take home.

There are many books to explore, so when entering the catalogue, we suggest you activate the Genre box at the bottom left corner. This box will help us to organise a more precise search, by categories, according to the age level or interests of our future readers. These categories are only in Finnish. We select and insert a few for you:

With these resources and those that we explore in our own research, we can encourage ourselves to discover new favourite authors and to take out many books to read as a family, to read and find excitement in being read to. With these resources and those that we explore in our own research, we can encourage ourselves to discover new favourite authors and to take out many books to read as a family, to read and to get excited about being read to. And, above all, this collection allows us to continue to give away new words.

Among these children’s books there is a great variety. There are books for pre-readers, books for early readers and books for advanced readers. For pre-readers we will find bilingual books, with pictograms; also, books that are not necessarily literature, such as the first books for chewing and expanding vocabulary, for example. For readers, we will be able to take home novels, classics, translations of well-known authors, fantasy books, adventures, comics, legends and folk tales, and many picture books. There are even several children’s books by well-known literary authors.

In the case of this collection, just under half of the collection are books translated from other languages (545). For example, a few classics like Tove Jansson (FI), Tuutikki Tolonen (FI), Timo Parvela (FI), Astrid Lindgren (SV) Sven Nordqvist (SV), Roald Dahl (UK), Mark Twain (EU), J. K. Rowling (UK), Lauren Child (UK), Cornelia Funke (DE), Hans Christian Andersen (DK), Eric Carle (EU). This is in addition to a number of books by major audio-visual companies.

Among the 863 books by Spanish-speaking authors and illustrators were: Isol Misenta (AR), Isidro Ferrer (ES), Paloma Valdivia (CL), Micaela Chirif (PE), Andrés Guerrero (ES), Graciela Montes (AR), Jordi Sierra i Fabra (ES), Luis Pescetti (AR), Ivar da Coll (CO), Elvira Lindo (ES), Manuel Marsol (ES), Jairo Aníbal Niño (CL), Emma Wolf (AR), María Cristina Ramos Guzmán (AR), María Teresa Andruetto (AR), María José Ferrada (CL), Pep Bruno (ES), Daniel Nesquens (ES) among a few others. We encourage you to get to know their works!

Lukupesä, “Reading Nests”, is Kulttuurikeskus Ninho’s new project for the promotion of children’s literature and the inclusion of families. The project offers mothers, fathers and other stakeholders a holistic programme to support and develop reading practices in Spanish, Portuguese and other minority languages. Our Lukupesä is made up of a series of training sessions and workshops around the beautiful topic of early childhood reading. At the same time, it will help communities to take advantage of existing infrastructure and services in the city (e.g., libraries and their collections) that are not always so accessible from a migrant perspective.

Another component of Lukupesä will be guided tours through the children’s book collections in HelMet by means of short online sessions in the spring and autumn, where we hope to search together with other families for children’s books to read at home. The sessions will provide a meeting point with practical information on how best to find good books and authors for children’s age levels and interests.

For more information, we invite you to stay tuned to our social media where we will share these events: Kolibrí Festivaali Facebook or Instagram: @kolibrifestivaali.

In our case, children’s literature in Spanish and Portuguese, books from Latin American publishers represent a much smaller number in the HELMET collection than those published in Spain or Portugal. From Kulttuurikeskus Ninho and with the support of the Latin American embassies in Finland, we are working to expand the diversity and quantity of books for children together we have added more than 100 new titles in recent years.

Remember, the more books we take home, the more effort HelMet will put into caring for and growing these collections. Long live this growing reading community!

Happy searching and happy reading!

Lau Gazzotti, Adriana Minhoto, Verónica Miranda, Andrea Botero y toda la gente linda que hace Kulttuurikeskus Ninho ry www.ninho.fi y Kolibrí Festivaali www.kolibrifestivaali.org.

Lau Gazzotti, Adriana Minhoto, Verónica Miranda, Andrea Botero and all the beautiful people of Kulttuurikeskus Ninho ry www.ninho.fi y Kolibrí Festivaali www.kolibrifestivaali.org.

In English below

Nos vemos parados em frente à estante da biblioteca do bairro, um pouco frustrados, pensando: porque encontro poucos livros infantis nas línguas minoritárias, como o português aqui? A resposta para essa pergunta, que também e válida para outros idiomas menos falados, é que a maioria dos livros estão guardadas nos depósitos do Helmet apenas esperando nossa reserva para os levarmos para casa.

Então, como fazer para que tenhamos acesso a eles e possamos leva-los para casa? É justamente sobre isso que vamos falar neste artigo! Vamos compartilhar nossa experiência com a coleção de literatura infantil em português do Helmet, uma coleção com mais de 400 livros. Esperamos que com esse material, possamos ajudar outras famílias a encontrarem exemplares em seus próprios idiomas.

A maneira mais eficaz é usar o site da Helmet é utilizando nosso número de usuário da biblioteca, ou com nossos filhos usando o número deles. Certamente já estamos habituados com o mecanismo de busca do sistema para encontrar algo de nosso interesse, usando o nome de um autor ou obra.

Porém, com a literatura infantil, sabemos por experiência própria que essa busca não é fácil. Temos que nos familiarizar com ela para tentarmos encontrar recomendações para a idade das crianças. Por exemplo, ao navegar no site Helmet (em finlandês, sueco ou inglês) com a palavra-chave “literatura infantil portuguesa” ou termos semelhantes, chega-se a um resultado incrível: (0) zero sugestões. Como é possível?

A busca de literatura em línguas minoritárias, é um pouco mais complexa. A isso se soma o fato de que os bibliotecários nem sempre estão preparados para ajudar às famílias neste imenso mundo da literatura infantil e muito menos dos livros em português, ou qualquer língua que não sejam as nacionais ou inglês.

Mesmo um pouco mais “escondidas”, as coleções de língua minoritária existem. Sim, elas existem! No caso de literatura infantil em português neste momento, em fevereiro de 2021, encontramos 412 livros infantis e 36 livros juvenis. Este número varia mensalmente e vale consultar o que há de novo aqui (helmet.fi).

O melhor caminho para encontrar o que buscamos é se familiarizar com o site de Helmet e encontrar a opção “busca avançada”. Assim como na busca de um tesouro, precisamos de uma senha! Neste caso, ela é um é um asterisco (*). Sim, você o verá nas diretrizes dos Kolibríes na imagem abaixo.

Atenção ao Kolibrí amarelo! Em Hakusana/keyword: vamos colocar (*) asterisco. E em kieli/language colocamos português. Depois de fazer isso, basta clicar em “buscar”. Assim, teremos toda a coleção de literatura infantil e juvenil disponíveis para que possamos escolher e levar para casa.

Depois que clicar em busca, aparecerão muitos livros para explorar, por isso, sugerimos ativar a caixa Genre localizada no canto inferior esquerdo. Selecionar esta caixa ajudará, de maneira muito simples, a organizar uma pesquisa mais precisa, por categorias que se referem à idade ou interesses de futuros leitores. Infelizmente, os gêneros estão disponíveis apenas em finlandês, mas nós traduzimos alguns para você:

Com esses recursos e com os que vamos conhecendo ao usar a ferramenta de busca, podemos nos animar a descobrir novos autores e reservar muitos livros para lermos em família. O site também permite fazer uma lista de livros favoritos para as próximas leituras e solicitar para que cheguem na biblioteca mais perto de casa ou do trabalho, o que for mais conveniente. Com certeza, esta coleção nos permite que continuemos aprendendo palavras novas com nossos filhos.

De certo, há uma grande variedade de livros infantis que vão desde livros para pré-leitores, livros bilíngues, livros com pictogramas, livros para primeiros leitores e até para leitores avançados, como romances, clássicos, traduções de autores reconhecidos, livros de fantasia, aventuras, histórias em quadrinhos, lendas e contos populares e muitos livros de figuras. Além disso, há livros que não são literatura, como os primeiros livros para morder e expandir o vocabulário, por exemplo. Existem até vários livros de autores reconhecidos de literatura adulta que se dispuseram a escrever para crianças.

No caso dos livros em português, dos 412 livros juvenis e infantis que encontramos, 118 são traduções para o português. Por exemplo, Tove Jansson, Astrid Lindgren, Antoine Saint Exupéry, Beatrice Alemagna, J. K. Rowling, Hans Christian Andersen, Hergé, para citar alguns. Além de livros das grandes empresas de cinema e animação.

Entre os 256 livros de autores e ilustradores que falam e escrevem português, encontramos Yara Kono, Catarina Sobral, Madalena Matoso, Ana Saldanha, Joana Estrela, Ciça Fittipaldi, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, Luísa Ducla Soares, Fernando Pessoa, Rui Lopes, David Machado, José Saramago, Jorge Amado, Alice Vieira, Ana Maria Machado, Rui de Oliveira, entre outros.

Lukupesä, “sala de leitura em tradução literal ou ninhos de leitura” é o novo projeto de Kulttuurikeskus Ninho para a promoção da literatura infantil e inclusão das famílias. O projeto oferecerá aos pais e outros interessados um programa para apoiar e desenvolver suas práticas de leitura na língua de herança. Nosso Lukupesä é composto por uma série de seções de capacitação e oficinas sobre este tema tão lindo e importante como é a leitura para primeira infância. Por sua vez, também ajudará as comunidades para aproveitar a infraestrutura e serviços já existentes na cidade (como por exemplo as bibliotecas e suas coleções) que as vezes parecem não ser tão acessíveis da perspectiva dos imigrantes.

Outro ponto importante do Lukupesä serão as visitas guiadas pelas coleções de livros infantil no Helmet por meio de seções curtas e online a serem realizadas na primavera e outono, onde esperamos ajudar na busca de livros infantis para ler em casa. Os encontros oferecerão um lugar com informação prática sobre a melhor forma de encontrar bons exemplares de acordo com idade e interesse.

Para mais informações, convidamos a todos a curtirem nossas redes sociais, onde vamos compartilhar os eventos Kolibrí Festivaali Facebook e Instagram: @kolibrifestivaali.

Em nosso caso, a literatura infantil em espanhol e português de livros de editoras da América Latina representam uma quantidade pequena na coleção do Helmet em comparação aos exemplares da Espanha ou Portugal. Nós do Kulttuurikeskus Ninho com o apoio das Embaixadas da América Latina na Finlândia, estamos trabalhando para aumentar a diversidade e quantidade de livros para a infância e juntos já somamos mais de 100 títulos novos entregues nos últimos anos.

Para deixar sugestões sobre a novos livros, podemos acessar este link.

Lembrem-se que quanto mais livros em português levamos para casa, mais esforços o Helmet dedicará para cuidar e fazer crescer estas coleções, vamos aumentar a demanda!

Viva esta nova comunidade de jovens leitores!

Boas buscas e boa leitura!

We find ourselves standing in front of the bookshelf of the neighbourhood library, a little frustrated, thinking: why do I find so few children’s books in minority languages like Portuguese here? The answer to this question, which is also valid for other less spoken languages, is that most of the books are stored in the Helmet storage facilities just waiting for our reservation to take them home.

So, how do we make sure we have access to them and can take them home? That is precisely what we are going to talk about in this article! We will share our experience with Helmet’s collection of children’s literature in Portuguese, a collection of over 400 books. We hope that with this material, we can help other families to find copies in their own languages.

The most effective way to use the Helmet website is by using our library user ID, or with our children using their user ID. Certainly, we are already used to the system’s search engine to find something of our interest using the name of an author or work.

However, with children’s literature, we know from experience that this quest is not easy. We have to familiarise ourselves with it to try and find recommendations for the children’s age level. For example, browsing the Helmet website (in Finnish, Swedish or English) with the keyword “Portuguese children’s literature” or similar terms, yields an incredible result: (0) zero suggestions. How is this possible?

The search for literature in minority languages is a little more complex. Added to this is the fact that librarians are not always prepared to help families in this immense world of children’s literature, let alone books in Portuguese, or any language other than national or English.

Even a little more “hidden”, minority language collections do exist. Yes, they do exist! In the case of children’s literature in Portuguese at the moment, in February 2021, we found 412 children’s books and 36 young adult books. This number varies each month and it is worth checking what is new here (helmet.fi).

The best way to find what we are looking for is to familiarise ourselves with the Helmet website and find the “advanced search” option. Just like in a treasure hunt, we need a password! In this case, it is an asterisk (*). Yes, you will see it in the Kolibríes guidelines in the image below.

Pay attention to the yellow Kolibrí! In Hakusana/keyword, we will insert (*) asterisk. And in kieli/language, we will insert Portuguese. After that, press “Search”. We will have then the entire collection of children’s and young adult books available for us to choose from and take home.

Once you click search, many books will appear for you to explore, so we suggest activating the Genre box located in the bottom left corner. Selecting this box will help, in a very simple way, to organise a more precise search by categories that refer to the age or interests of future readers. Unfortunately, the genres are only available in Finnish, but we have translated some for you:

With these resources and those that find by using the search engine, we can encourage ourselves to discover new authors and book many books to read as a family. The site also allows you to make a list of favourite books for future readings and request them to arrive at the library nearest your home or work, whichever is most convenient. Certainly, this collection allows us to continue learning new words with our children.

There is certainly a wide variety of children’s books ranging from books for pre-readers, bilingual books, books with pictograms, books for early readers and even for advanced readers, such as novels, classics, translations by renowned authors, fantasy books, adventures, comics, legends and folk-tales and many picture books. In addition, there are books that are not literature, like the first books to chew on and expand vocabulary, for example. There are even several books by well-known literary authors who have taken the time to write for children.

In the case of books in Portuguese, of the 412 young adult and children’s books we found, 118 were translations into Portuguese. For example, Tove Jansson, Astrid Lindgren, Antoine Saint Exupéry, Beatrice Alemagna, J. K. Rowling, Hans Christian Andersen, Hergé, to name but a few. As well as books from the big films and animation companies.

Among the 256 books by authors and illustrators who speak and write Portuguese, we find Yara Kono, Catarina Sobral, Madalena Matoso, Ana Saldanha, Joana Estrela, Ciça Fittipaldi, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, Luísa Ducla Soares, Fernando Pessoa, Rui Lopes, David Machado, José Saramago, Jorge Amado, Alice Vieira, Ana Maria Machado, and Rui de Oliveira, among others.

Lukupesä, “reading room” in literal translation or “reading nests” is Kulttuurikeskus Ninhos’s new project for the promotion of children’s literature and inclusion of families. The project will offer parents and other stakeholders a programme to support and develop their reading practices in the heritage language. Our Lukupesä is made up of a series of training sections and workshops on this beautiful and important topic as early childhood reading. In turn, it will also help communities to take advantage of already existing infrastructure and services in the city (such as libraries and their collections) that sometimes seem not so accessible from the perspective of immigrants.

Another important feature of Lukupesä will be guided tours of the children’s book collections in Helmet through short, online sections to be held in the spring and autumn, where we hope to help in the search for children’s books to read at home. The meetings will offer a place with practical information on how best to find good books according to age level and interests.

For more information, we invite you to stay tuned to our social networks, where we will share the events on Kolibrí Festivaali Facebook and Instagram: @kolibrifestivaali.

In our case, children’s literature in Spanish and Portuguese from books by Latin American publishers represent a small number in Helmet’s collection compared to copies from Spain or Portugal. We at Kulttuurikeskus Ninho with the support of the Latin American Embassies in Finland, are working to increase the diversity and quantity of books for children and together we have already added over 100 new titles in recent years.

To leave suggestions about any new books, login at this link.

Remember, the more books in Portuguese we take home, the more effort Helmet will put into looking after and growing these collections, let’s increase demand!

Long live this new community of young readers!

Happy searching and happy reading!

Lau Gazzotti, Adriana Minhoto, Verónica Miranda, Andrea Botero e todas as pessoas lindas que fazem parte do Kulttuurikeskus Ninho www.ninho.fi e Kolibrí Festivaali www.kolibrifestivaali.org.

Lau Gazzotti, Adriana Minhoto, Verónica Miranda, Andrea Botero and all the beautiful people who are part of Kulttuurikeskus Ninho www.ninho.fi and Kolibrí Festivaali www.kolibrifestivaali.org.

(In English below)

Idag, i februari och mars, vi firar våra modersmål, språk i allmänhet, och de möjligheter och glädje de språk som vi talar ger oss i våra dagliga liv. Idag talas det över 140 språk som modersmål i Finland, vilket betyder att vi har en mängd olika sätt att uttrycka oss och se världen omkring oss.

Luckan är ett finlandssvenskt kultur- och informationscentrum där vi jobbar med en bred repertoar av kultur, utställningar och evenemang, barnkultur, ungdom och integration. För oss är svenskan ett viktigt språk och det språk vi använder mest. Det är språket som binder oss samman, modersmål för många av oss och våra kunder och ett fönster till Svenskfinland för de som integreras på svenska och lär sig svenskan som andra, tredje, eller fjärde språk, och så vidare. I vårt dagliga arbete möter vi också människor som talar engelska, finska, franska, arabiska, ryska, somaliska, och många andra språk. Dessa språk är våra kollegors, kunders, samarbetspartners och besökares modersmål eller andra språk som de använder.

Att tala olika språk betyder att vi kan kommunicera med varandra och lära oss om varandra och olika sätt att uppfatta världen, men språk kan också skilja oss från varandra. Språkfrågor som vi stöter på i vårt arbete kan handla om valet mellan finska och svenska, om hur man kan säkerställa att barnen med annat hemspråk lär sig tillräckligt bra svenska i skola,, eller om man borde uppmana barn att lära sig hemspråket i ett samhälle där språk inte alltid ses som en rikedom.

Språkval vi gör i våra dagliga liv påverkar andras liv och vi måste vara medvetna om det, speciellt om vi jobbar med människor som har andra modersmål, men också annars, eftersom våra språkval kan betyda att vi utesluter andra som skulle vilja delta och bidra.

Det finns olika sätt att inkludera språk i våra arbete och hobbyer för att öppna upp våra svenska eller finska rum till personer med annat modersmål och språk. Flerspråkig information och marknadsföring fast verksamheten sker på ett språk låter folk veta vad som pågår. Att hälsa på flera språk och klargöra att kommentarer och frågor kan ställas på olika språk, synliggör flerspråkigheten för dem som talar majoritetsspråket, samtidigt som det blir lättare att använda det språk som känns bäst för en själv. Korta sammanfattningar på olika språk kan väcka tankar genom att uttrycka det som diskuteras på ett nytt sätt, medan de också säkerställer förståelsen för alla som deltar. Att hålla tal och visuella presentationer på olika språk kan göra det enklare att följa med och färdigskrivna texter och presentationer kan även sändas ut på förhand för deltagare att kunna förbereda sig, oberoende av språk. Lättspråk gör innehållet mer tillgångligt, men att tala lätt betyder inte bara att man talar långsamt och tydligt, utan det är ett kunskap som man lär sig.

Att vara språkmedveten kräver lite extra framåt tänkande från de som talar majoritetsspråket, men man blir snabbt van och belöningen blir större än besväret. Det tar tid att lära sig ett nytt språk, så att öppna upp verksamheter och rum till invandrare och andra som lär sig ett nytt språk ligger hos de som redan talar det språket de andra lär sig, både språkmässigt och i allmänhet. Vi behöver granska våra egna attityder och fördomar angående språk. Folk som inte talar svenska eller finska perfekt, kan av andra uppfattas som enklare, även när vi vet att det är inte sant. Transspråkande, att använda all ens språkkunskaper, oberoende av de imaginära gränser som vi uppfattar mellan olika språk, kan också uppfattas negativt, att man blandar språk. En öppen, positiv attityd till språk betyder att vi lär oss mera, förstår mera, och inkluderar fler, samtidigt som den förstärker allas språkliga och kulturella identitet.

Today, and during the months of February and March, we celebrate our mother tongues, languages in general, and the possibilities and joy the languages we speak give us in our daily lives. Over 140 languages are spoken in Finland today as mother tongues, opening up a multitude of ways in which we can express ourselves and perceive the world around us.

Luckan is a Swedish-language information and cultural centre, working with a wide variety of culture, exhibitions and events, children, young people, and integration, and for us at Luckan, Swedish is of course an important language, the one we use the most. It is the language that ties us together as a community as well as a place of work, the mother tongue of many of our colleagues and customers, and a window to the Finland-Swedish community for many of the people integrating in Finland and learning Swedish as a second, third, or fourth language, and so on. In our daily work, however, we come across English, Finnish, French, Arabic, Russian, Somali, and many other languages as well, whether they be the mother tongues or spoken languages of our colleagues, customers, cooperation partners, or visitors.

While languages mean we can communicate with one another and learn about each other as well as about different ways of perceiving the world, they can also separate us from one another. Language-related questions and issues we come across in our work include questions about whether to learn Swedish or Finnish to be able to become a part of the local community, how to ensure that children with other languages as their mother tongue grow up knowing enough Swedish, and whether to encourage a child to learn the home language in a society that doesn’t always see languages as a richness.

Language choices we make in our everyday lives affect the lives of others, and we must be conscious of them, especially when we work with people speaking a different language, but also when we don’t, as not thinking about the language choices we make can mean we exclude people who would like to participate and contribute.

There are different ways to include languages in our workplaces and hobbies, and to open up our Swedish-language or Finnish-language spaces to people who have different mother tongues and speak different languages. Multilingual information and marketing materials are an important way of letting people know what is going on, even if the languages spoken at the events and spaces are Swedish or Finnish. Greeting people in different languages and clearly stating that comments are welcome in as many languages as possible makes multilingualism visible for those speaking the majority language, as well as making asking questions and changing languages if necessary easier for those who cannot necessarily participate in the majority language. Short summaries in different languages can provide food for thought in expressing the things said in a different way, as well as making sure everyone understands what is being discussed. Speaking and presenting slides in two different languages makes following easier, and slides and texts can even be sent to participants beforehand, giving them time to prepare, regardless of their language. Speaking simple Swedish or Finnish makes understanding more accessible, but learning a simple language is not just speaking more slowly with clearer enunciation, but a skill in itself, meaning that one has to take the time to learn it.

Language-consciousness requires extra effort and forward-thinking from the part of the majority language speakers, but when it becomes a habit, it comes naturally, and the rewards outweigh the inconveniences. Language learning takes time and effort, so the responsibility of opening up activities and spaces to immigrants and other language-learners, language-wise as well as otherwise, lies within those who already speak the languages others are learning. We need to take the time to examine our preconceptions and prejudices. People speaking less than perfect Swedish or Finnish, can by some be perceived as being simpler, even when we know that this is not the case. Translanguaging, using all of one’s language skills in several languages, regardless of the boundaries that we imagine to exist between languages, is an important resource in communication, but is often also viewed negatively, as mixing languages. An open and positive attitude towards languages and language use means more learning, understanding, and inclusion, as well as strengthening the language and cultural identities of all involved.

Skrivaren jobbar som en integrationskoordinator och ambulerande handledare för familjer med barn i svensk skola eller dagis på Kompetenscentret för svensk integration inom Luckan integration, med fokus på social integration. Du kan ta kontakt i frågor gällande svensk integration, familjer och att öppna upp verksamheter för icke-svenskspråkiga på swedish@luckan.fi. För mer information om Luckans integrationsarbete se integration.luckan.fi.

The writer works as an integration coordinator and guidance counselor for families with children at Swedish-language schools and daycare centres at the Competence Centre for Swedish Integration at Luckan Integration, focusing on social inclusion. You can be in touch with questions related to Swedish integration, families, and opening up the activities of organisations to non-Swedish speakers at swedish@luckan.fi, and find more information on the work Luckan does at integration.luckan.fi.

In November 2009, on Universal Children’s Day, a group of Inari Saami teachers, parents and children travelled to the capital to meet Finnish politicians including President Halonen. The purpose was to campaign for more school books in Inari Saami language. An official complaint about the situation was presented to the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman. The situation has gradually improved since but there is still a severe lack of culturally appropriate learning materials for Inari Saami speaking children.

Anarâškielâ Servi ry (Inari Saami Language Association) was established in 1986 by Veikko Aikio, Ilmari Mattus and Matti Morottaja. The Inari Saami language nest was later established because there was a genuine concern the Inari Saami language might disappear and be lost forever. At first learning materials for Inari Saami speaking children were so scarce, the language nest staff had to translate books from different cultures by glueing the new text on books to cover the original story. One might wonder why Northern Saami books were not used as there was already a decent selection of children’s literature available. For an outsider it may be hard to understand that these are two different although closely related languages. The idea would be similar to suggesting to Estonians to start learning Finnish, a bigger language, instead of their own language.

There are more books and materials to choose from in Northern Saami because there are approximately 30,000 Northern Saami speakers. It is the majority Saami language spoken in Finland but also a language spoken in Norway and Sweden, so resources are not limited to Finland alone. There are still only approximately 450 Inari Saami speakers, along with Skolt Saami, it’s still a minority’s minority language amongst Saami speaking people. All three languages are represented in the local school in Inari. I wanted to help with making learning materials for Inari Saami children because my children attended the language nest. The language nest is a total immersion language nursery, where the core work for language revitalisation is done. Below is a link to a documentary telling about the language nest and the language revitalisation work of Anarâškielâ Servi ry. After leaving the language nest the children usually progress to the Piäju, similar to the language nest but for older preschool children. From there the children can progress to school, where they can continue their education in Inari Saami language. As more children progress from the language nest, the number of Inari Saami speaking people has increased since the making of this video: Reborn (YouTube).

I have been cooperating with Anarâškielâ Servi ry to publish bilingual Inari Saami/English children’s books to help the learning materials situation. I write the stories in English, illustrate the books and then they are translated into Inari Saami by Petter Morottaja, the son of one of the main people in the revitalisation work here in Inari. My wife is also Inari Saami and a folklorist, so she is able to help me with the stories. First of all I wrote and illustrated a book for older children called “The Forgetful Squirrel” and was then asked to make books for younger children. The main character of the original book, an Inari Saami boy called Sammeli, was the inspiration for the series of books which tell of him and his adventures in the “Eight Seasons of Lapland”. The books are in Inari Saami to provide much needed materials for the children learning Inari Saami in the language nests and local school. This way there are culturally appropriate learning materials for Inari Saami speaking children, that also offer them the opportunity to learn English. Tourists who speak English can purchase the books from Sámi Duodji, Siida museum, Hotel Kultahovi in Inari and other places including Arktikum in Rovaniemi and online from Anarâškielâ servi ry.

This way they can learn about the local language and culture, and the revenue can help to fund further books and learning materials for the future.

When I was asked to write this blog, I read about the philosophy behind

Culture for All and was proud to contribute to something so worthwhile. I thought about a seminar for the project “Toward a More Inclusive and Comprehensive Finnish Literature” I was invited to attend, hosted by the Finnish Literature Society (SKS). The seminar led to an anthology “Opening Boundaries: Toward Finnish Heterolinational Literatures”, in which I was very happy to be included. It’s wonderful that there is a concerted effort being made to foster and promote the inclusion of immigrants in Finland and to celebrate their contribution to Finnish society. People have different talents, whether they are writers or artists or make a positive contribution to the wealth of the country in some other way. Similarly Finnish people living in other countries can take their ideology and talents with them to a new country, where they have the chance to make a positive contribution to their new environment, whilst sharing and promoting knowledge of their home country. In the acknowledgements, editor Mehdi Ghasemi wrote “Without their invaluable support, the implementation of the project and the publication of this book would not have been possible.”

There is an African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.” Without the persistence and endeavour of countless people working for Anarâškielâ Servi ry in the language nest or Piäju, school teachers or kind people providing grants for Inari Saami literature, there would be even less learning opportunities than presently. Chances are the Inari Saami language would have disappeared like other forgotten Saami languages. Even if you just took the time to read this blog, you made a contribution. One more person understands the need for Inari Saami speaking children to have learning materials in their own language.

Lonottâllâm – Sharing, Autumn story (PDF)

The children, who have attended the language nest, Piäju and school in their own language, have now started to make their own contribution to Inari Saami culture. Some have written articles for the digital magazine Loostâš, Wikipedia articles and translated books from other languages into Inari Saami to increase the volume of literature available. Reading about different cultures is a very good way to learn and increase understanding and appreciation of those cultures. If Finnish people had an opportunity to read Inari Saami literature in Finnish, they would have a chance to learn about a language and culture indigenous to Finland, adding to the collective wealth of the country. In the same way that Finnish literature and books from writers of other countries have added to the wealth of Inari Saami literature, Inari Saami children should have the chance to see themselves represented in Finnish culture and shown in a positive light. Usually Saami children only see themselves in adverts encouraging tourism to Lapland. They grow up seeing Saami people shown often unfairly and inaccurately, sometimes even disparagingly, on postcards or comedy programmes from which negative stereotypes can endure for decades.

There is still a chronic shortage of culturally appropriate learning materials for Inari Saami speaking children, and funding for Anaraskiela Servi ry is a constant struggle. If bilingual Finnish/Inari Saami literature was included in the school curriculum, there would be sufficient funding for books, and both Finnish and Inari Saami children would benefit.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child covers essential rights regarding social welfare including political, social, economic and cultural rights. It states that children should have the right to develop to the fullest. Inari Saami speaking children should have the right to learning materials in their own language in their indigenous country, and Finland should give them this opportunity.

A quote from American philosopher William James says: “Act as if what you do makes a difference. It does.” It’s very easy though to lose motivation when you don’t feel valued or appreciated. We are all to some extent products of our environment, and when Inari Saami speaking children aren’t represented and made to feel they matter, they are at an immediate disadvantage and consequently may not accomplish their potential.

Finland is often applauded for having one of the most progressive education systems in the world. Supporting Inari Saami language revitalisation and the indigenous children of its country, would give Inari Saami children a voice and a chance to add to the narrative of Finland.

Lee D Rodgers

Lee Rodgers is originally from Manchester, where he worked as an artist before attending university in Manchester and Helsinki. He lives in Inari with his Inari Saami wife and family. He has been cooperating with Anarâškielâ Servi ry, The Inari Saami Language Association to help with Inari Saami language revitalisation. Lee Rodgers has written a series of bilingual Inari Saami/English books based on the adventures of a young Inari Saami boy called Sammeli in the “8 Seasons of Lapland”. For more information please contact rodgerslee9@gmail.com or www.anaraskielaservi.fi.

(in English below)

Suomessa on yhä enemmän perheitä, jotka ovat monikielisiä. Suomessa on yhä enemmän lapsia, jotka kasvavat monikielisessä ympäristössä.

Yli 400 000 Suomessa asuvaa ihmistä puhuu äidinkielenään jotain muuta kuin suomea, ruotsia tai saamea. Suurimmat kieliryhmät ovat venäjä, viro, arabia, englanti ja somali.

Tilastokeskuksen tilastoissa puhutaan vieraskielisen väestön määrästä, joka on kasvanut voimakkaasti. Vielä 2000-luvun alussa vieraskielisiä asui Suomessa reilut satatuhatta, nyt määrä on yli kolminkertainen.

Olen miettinyt kirjastojen mahdollisuuksia palvella monikielisiä ja vieraskielisiä yhteisöjä. Asia nousi ajankohtaiseksi viime marraskuussa, kun valmistelin keskustelua teemasta suomalais-ruotsalaisen kulttuurikeskus Hanasaaren kulttuuripolitiikan päivään.

Kirjastojen työntekijöistä vain noin prosentti puhuu äidinkielenään jotain muuta kuin suomea tai ruotsia. Tämä hätkähdyttävän pieni luku tuli esiin kirjastoalan järjestöjen tekemässä kyselytutkimuksessa.

Miksi kirjastoissa on töissä niin vähän vieraskielisiä? Pitääkö olla huolissaan kirjastojen kyvystä palvella monikielisiä yhteisöjä?

Oma mututuntumani on, että kovin on vaikeaa työllistyä kirjastoon, jos ei hallitse täydellisesti suomen kieltä.

Eräs kirjastoalan oppilaitos järjesti joitakin vuosia sitten muuntokoulutuksen korkeakoulutetuille maahanmuuttajille. Muuntokoulutuksen piti pätevöittää kirjastoalan työtehtäviin. Heistä hyvin harva loppujen lopuksi työllistyi kirjastoon.

Kulttuuriala ja myös kirjastoala näkee itsensä mielellään moninaisena ja kaikille avoimena. Alan työntekijöitä yhdistävät tasa-arvon ja yhdenvertaisuuden ihanteet.

Niin kauan kuin työntekijöiden edustama maailma on hyvin kaukana yhteiskunnassa vallitsevasta väestörakenteesta, emme voi puhua moninaisuuden toteutumisesta.

On tärkeää, että eri ammateissa toimii erilaisia ihmisiä. Lukuisat tutkimukset kertovat, että eri-ikäisistä, eri sukupuolta olevista, erilaisista taustoista koostuvien ihmisten tiimit pääsevät usein parhaaseen lopputulokseen ja niiden kyky ongelmanratkaisuun on huomattavasti parempi kuin keskenään samanlaisten ryhmien.

Asiaan on herätty. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö julkaisi juuri Kulttuuripolitiikka, maahanmuuttajat ja kulttuurisen moninaisuuden edistäminen -työryhmän loppuraportin. Sen mukaan ”väestön moninaistuminen on otettava — huomioon kaikessa taide- ja kulttuuripoliittisessa suunnittelussa ja päätöksenteossa.”

Raportti esittää myös haasteen: ”taide- ja kulttuuriorganisaatioiden pitää tunnistaa syrjivät rakenteet ja rekrytointikäytännöt ja tunnustaa niiden eriasteinen olemassaolo omassa toiminnassaan.”

Käytännössä tämä tarkoittaa, että taide- ja kulttuurilaitoksiin, myös kirjastoihin, pitää palkata kaiken tasoisiin tehtäviin lisää monikielisiä ihmisiä ja lisää maahanmuuttajia.

Mitkä ovat kirjastoalan ”syrjivät rakenteet ja rekrytointikäytännöt”? En tiedä, mutta veikkaan, että yksi liittyy koviin kielivaatimuksiin.

Kirjasto on paljon muutakin kuin kirjat. Se on palvelu, joka tarjoaa sivistystä ja osaamista kaikille yhteisössä. Hyvän kirjastotyöntekijän edellytys ei voi olla täydellinen kielitaito.

Finland is home to an increasing number of multilingual families. Finland also has an increasing number of children who are growing up in a multilingual environment.

More than 400,000 people living in Finland speak a language other than Finnish, Swedish or Sami as their native language. The largest language groups are Russian, Estonian, Arabic, English and Somali.

The statistics of Statistics Finland show the number of foreign-language speakers, which has grown strongly. At the beginning of the 2000s, a little more than one hundred thousand foreign-language speakers lived in Finland; the number has now more than tripled.

Lately, I have been thinking about our libraries’ ability to serve multilingual and foreign-language communities. The issue became topical last November when I was preparing a discussion on the topic for Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre Hanaholmen’s Cultural Politics Dialogue Day.

Only about one per cent of all library staff speak a language other than Finnish or Swedish as their native language. This strikingly low figure came up in a survey carried out by library organisations.

Why are there so few foreign-language speakers working in libraries? Should we be concerned about our libraries’ ability to serve multilingual communities?

My personal feeling is that it is very difficult to get a job in a library if your command of Finnish is anything short of perfect.

Some years ago, a library institute organised conversion training for highly-educated immigrants. The conversion training was supposed to qualify the immigrants for work in libraries. In the end, very few of them were employed in a library.

The culture sector, much like the included library sector, likes to view itself as a diverse sector that is open to all. Employees in the sector share ideals of equality and non-discrimination.

However, as long as the world represented by these employees is a far cry from the demographic structure of our society, we cannot say that we have achieved diversity.

It is important that there are different kinds of people operating in different professions. Numerous studies show that teams of people of varying ages, genders and backgrounds often achieve the best results and have a much better problem-solving ability than uniform groups.

Decision-makers have become aware of this issue. The Ministry of Education and Culture recently published the final report of the working group on Cultural Policy, Immigrants and Promotion of Cultural Diversity. It states that “the diverse demographic structures must be reflected in all artistic and cultural-politic planning and decision-making”.

The report also poses a challenge: ”Artistic and cultural organisations must identify discriminatory structures and recruitment practices and recognise their varying degrees of existence in their own activities.”

In practice, this means that artistic and cultural institutions, including libraries, must employ more multilingual people and more immigrants for jobs at all levels.

What are the “discriminatory structures and recruitment practices” in the library sector? I do not know, but I am guessing one of them has to do with stringent language requirements.

The library is much more than just books. It is a service that provides education and knowledge for everyone in the community. Flawless language skills must not be a prerequisite for working in a library.

Rauha Maarno

Kirjoittaja on Suomen Kirjastoseuran toiminnanjohtaja.

The author is the Executive Director at Finnish Library Association.

[In English below]

Lasten ja nuorten lukemiseen kannustamiseksi tehdään työtä usealla taholla. Jo varhain aloitettu yhdessä lukeminen on tärkeää. Lukeminen on mukavaa aikuisen ja lapsen välistä yhdessäoloa mutta se myös kehittää lapsen kieltä ja puhetta, kuuntelun ja keskittymisen taitoa sekä sanavarastoa.

Riitta Salin peräänkuuluttaa omassa blogitekstissään vanhempiin kohdistuvaa työtä kun puhutaan oman äidinkielen säilyttämisen ja ylläpidon merkityksestä. Oman äidinkielen opettajat ovat tässä keskeisessä asemassa. Kirjastoilla taas on tarjota aineistoja, joilla voidaan tukea perheen yhteistä lukuharrastusta monilla kielillä.

Suomessa on meneillään useita valtakunnallisia lukemista edistäviä kampanjoita ja hankkeita. Lukuliike on hallitusohjelmaan kirjattu jatkuva ohjelma, jonka tavoitteena on edistää Suomessa asuvien lukutaitoa, lapset ja nuoret edellä. Lukuliike pyrkii laajentamaan lukutaidon käsitettä ja tuomaan esiin monilukutaitoa sekä monikielisyyttä. Tämän vuoden alusta opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö on antanut lasten ja nuorten lukemista ja lukutaitoa edistävien kirjastopalvelujen valtakunnallisen erityistehtävän Seinäjoen kaupunginkirjastolle.

Hyviä esimerkkejä käytännön lukutaitotyöstä on monia mutta tässä voidaan poimia esiin vaikka Niilo Mäki-instituutin Lukumummit –ja vaarit (Reading grandmas and grandpas: seniors reading with children at school). Lukumummi ja -vaari -kerhossa eri kulttuureista tulevat mummit ja vaarit lukevat lapsille kirjoja omalla äidinkielellä. Tapahtuma järjestetään iltapäivällä monikulttuurikeskusten kerhoissa. Lapset pääsevät tutustumaan oman kielen kirjoihin ja oppivat uusia sanoja mummien ja vaarien kanssa. Kerhoja on jo useilla paikkakunnilla eri puolilla Suomea.

Lapsille ja perheille tulee olla lukemista tarjolla eri muodoissa. Perinteinen paperinen lastenkirja on monille se rakkain mutta monikielisten digitaalisten aineistojen, e-kirjojen ja äänikirjojen, tarjonta ja käyttö lisääntyy ja kirjastojen tulee voida tarjota niitä asiakkailleen nykyistä helpommin. Tällä hetkellä kirjastojen e-aineistojen käyttäminen on asiakkaalle haastavaa, sillä ne ovat useilla eri palvelualustoilla. Tämä heikentää monikielisten aineistojen yhdenvertaista saavutettavuutta.

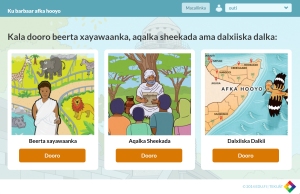

Monessa kunnassa varhaiskasvatus, koulut ja kirjastot ovat jo ottaneetkin käyttöön maksullisen Lukulumo – monikielisen kuvakirjapalvelun (Ruotsissa nimellä Polyglutt). Lukulumosta löytyy yli 300 suomenkielistä kuvakirjaa, joista monia voi kuunnella ja katsella yli 45 kielellä. Kirjat palveluun ovat valinneet lastenkirjallisuuden asiantuntijat. Lapset voivat kehittää niin suomen ja ruotsin kielen kuin myös oman äidinkielen taitojaan. Lapset voivat tutustua samaan kuvakirjaan omilla kielillään.

Pohjoismaat, Norja, Tanska ja Ruotsi, tarjoavat jo yhteistyössä monikielisiä e-kirjoja ja äänikirjoja asiakkailleen World Library –palvelussa. Monikielinen kirjaston on seurannut projektin etenemistä useita vuosia. Toivottavasti Suomen kirjastot voivat liittyä mukaan palveluun lähitulevaisuudessa ja näin saada valikoiman digitaalista aineistoa asiakkaidensa käyttöön.

Tammikuussa 2020 Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö myönsi 250 000 euron avustuksen kansallisen e-kirjaston selvityshankkeen käynnistämiseksi. Helsingin kaupunginkirjaston vetämän hankkeen tavoitteena on parantaa e-kirjojen alueellista saatavuutta ja kansalaisten yhdenvertaisuutta ja tasa-arvoa koko Suomessa. Kun lähitulevaisuudessa yleisten kirjastojen tarjoama laaja digitaalinen kokoelma on kaikkien yleisten kirjastojen asiakkaiden käytettävissä yhdeltä palvelualustalta, myös monikielinen aineisto on helpommin kaikkien saavutettavissa. Selvitystyön raportti julkaistaan helmi-maalikuussa 2021.

Monikielisen aineiston saavutettavuuden lisäksi on vielä kysyttävä miten yhteiskuntamme monimuotoisuus näkyy Suomessa julkaistavissa lastenkirjoissa. Lastenkirjat kuvaavat suureksi osaksi enemmistökulttuuria. Tätä näkökulmaa selvittää Goethe-instituutin lastenkirjallisuuden monimuotoisuushanke. Useassa Ruotsissa julkaistussa lastenkirjassa seikkailee jo monikulttuurisen ja monimuotoisen taustan omaavia lapsia. Lapsen ja nuoren olisi tärkeää löytää kirjoista samaistumisen kohteita, hänen elämästään tuttuja hahmoja ja tarinoita.

Efforts are being made in many areas to encourage reading among children and young people. It is important to start reading together with the child at an early age. Reading is a pleasant shared activity for an adult and child, and it also develops the child’s language and speech, listening and focusing skills and vocabulary.

In her blog post, Riitta Salin calls for measures aimed at parents in the context of retaining and maintaining one’s own native language. In this regard, native language teachers play an important role. Libraries, on the other hand, can offer materials that can support a family’s shared reading hobby in a variety of languages.

There are currently nationwide campaigns and projects under way in Finland to support reading. The Literacy Movement is a continuous effort laid down in the Government Programme, which aims to promote the literacy of Finnish residents, with a focus on children and young people. The movement aims to expand the concept of literacy and highlight multiliteracy and multilingualism. From the beginning of this year, the Ministry of Education and Culture has assigned the special national responsibility related to library services that promote reading and literacy among children to the Seinäjoki Public Library.

There are plenty of great examples, one of which is Niilo Mäki Institute’s Lukumummit ja -vaarit project (Reading grandmas and grandpas), which involves grandmothers and grandfathers from various cultures visiting schools to read books to children in their own native languages. The events are held in the afternoon in the context of club activities offered by multicultural centres. This introduces children to books in their own language and learn new words together with experienced readers. Many of these clubs have already been established throughout Finland.

Reading must be available to children and families in a variety of forms. Many love traditional printed children’s books best, but the offering and use of multilingual digital materials, e-books and audio books is increasing, which is why libraries must be able to make them more easily accessible to their customers. At present, accessing the e-materials of libraries can be a challenge to customers since they are scattered across multiple service platforms. This hinders the equal availability of such materials.

In many municipalities, early education, schools and libraries have introduced the multilingual picture book service Lukulumo (named Polyglutt in Sweden), which is subject to a fee. The service features more than 300 picture books in Finnish, many of which can be read and listened to in more than 45 languages. The books for the service have been selected by experts in children’s literature. Lukulumo enables children to develop their proficiency in Finnish, Swedish and their own native languages, for example by reading the same picture book in many languages.

The Nordic countries of Norway, Denmark and Sweden have already joined forces to offer multilingual e-books and audio books to their customers through the World Library service. The Multilingual Library has been following the project’s progress for several years. Hopefully, Finnish libraries will be able join the service in the near future and make its selection of digital materials available to their customers.

In January 2020, the Ministry of Education and Culture awarded a grant of €250,000 to initiate a project to investigate the possibility of establishing a national e-library. The aim of the project run by the Helsinki City Library is to improve the regional availability of e-books as well as equality and equal opportunity among citizens throughout Finland. Making the vast digital collections offered by public libraries available to all library customers through a single service platform in the near future will ensure that everyone can access multilingual materials much easier than before. The investigation report will be published between February and March 2021.

In addition to securing the accessibility of multilingual material, we must also ask ourselves how the diversity of our society is reflected in the children’s books published in Finland. Children’s books largely depict the majority culture. This perspective is being explored by the Goethe Institute’s project focusing on diversity in children’s literature. Many children’s books published in Sweden already feature children with a diverse and multicultural background as their protagonists. It would be important for children and young people to discover identifiable things in the books they read, along with familiar characters and stories.

***

Kirjoittajat Eeva Pilviö ja Riitta Hämäläinen työskentelevät Monikielisen kirjaston informaatikkoina Helsingin kaupunginkirjastossa. Monikielinen kirjasto on opetus-ja kulttuuriministeriön rahoittama palvelu.

Kirjoittajat Eeva Pilviö ja Riitta Hämäläinen työskentelevät Monikielisen kirjaston informaatikkoina Helsingin kaupunginkirjastossa. Monikielinen kirjasto on opetus-ja kulttuuriministeriön rahoittama palvelu.

The writers Eeva Pilviö and Riitta Hämäläinen work as information specialists at the Multilingual Library of the Helsinki City Library. The Multilingual Library is a service funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Monikielisyydestä puhuttaessa on kuitenkin koko ajan otettava huomioon yksilöllinen ulottuvuus. Kuvitelma siitä, että yhdellä ihmisellä voi olla vain yksi äidinkieli, oli jonkin aikaa vallitsevana kansallisvaltioiden nousun myötä 1800-1900-luvuilla, ja aiheutti paljon pahaa vähemmistökielille suomalaisessakin yhteiskunnassa. Ajateltiin jopa, että useamman kielen oppiminen jo lapsena on haitallista ihmisille. Vaikka tutkimus sittemmin on osoittanut täysin vastakkaista, yksikielisyyttä ihannoivat käsitykset elävät edelleen. Käsitys elää voimakkaana Venäjän nykyisen hallinnon kielipolitiikassa, joka jatkuessaan voi johtaa suhteellisen nopeasti vähemmistökielten kuolemiseen.

Ruotsissa Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, maan suurin humanististen ja yhteiskuntatieteiden rahoittaja, julkaisi äskettäin vuosikirjan RJ:s årsbox 2019: Det nya Sverige, joka koostui muutaman kymmenen sivun katsauksista eri asioihin. Yksi katsaus käsitteli kieliä, ja sen on kirjoittanut Mikael Parkvall Tukholman yliopistosta. Katsaus on kiinnostava ja sisältää hyödyllistä tietoa. Toisin kuin valtio Suomessa, Ruotsin valtio ei rekisteröi kansalaisten kieliä. Niinpä Parkvall on tehnyt paljon työtä selvittääkseen Ruotsissa puhuttuja kieliä 2010-luvulla; hän julkaisi tuloksiaan kirjassa Sveriges språk i siffror (2015). Selvityksen mukaan suurimpia äidinkieliä ruotsissa v. 2012-13 olivat suomi, arabia, serbokroaatti-ryhmä (Jugoslavian hajoamisen jälkeen poliittisista syistä erillisiksi ajautuneet kielet), kurdi, puola ja espanja.

Kielten luokittelun hankaluus käy Parkvallin katsauksesta ilmi: Ruotsin virallisessa tilastossa tunnistetaan vain yksi saamen kieli, vaikka kielitieteilijät nykyisin erottavat yhdeksän saamen kieltä, joista useita puhutaan Ruotsin alueella. Ruotsin eri murteita ei eroteta toisistaan eri kieliksi, mutta suomi ja meänkieli erotetaan, vaikka moni kielitieteilijä pitää niitä saman kielen murteina. Kuten tästäkin näkyy, kielten luokitteluun julkisessa hallinnossa vaikuttavat aina myös politiikka ja kulttuuriperintö.

Se mikä Parkvallin katsauksesta melko yllättävästi puuttuu, on yksilöllinen monikielisyys. Hän on selvittänyt perusteellisesti ruotsalaisten äidinkieliä, mutta ei puhu lainkaan siitä, millaista yksilöllistä monikielisyyttä Ruotsissa on (paitsi se, että jotain muuta kieltä äidinkielenään puhuvat osaavat tavallisesti myös ruotsia). Hän suhtautuu pessimistisesti monikielisyyden mahdollisuuksiin säilyä. Tässä minua kiinnostaa vertailu antiikin ja keskiajan Sisiliaan, jota olen itse tutkinut. Siellä kaksi kieltä, kreikka ja latina, säilyivät ainakin tuhat vuotta rinnakkain, paikoittain todennäköisesti 1500 vuotta. Kyse oli toki kahdesta korkean prestiisin kielestä, joita molempia käytettiin (eri aikoina) kirkon ja hallinnon piirissä.

On kiinnostava nähdä, miten tilanne kehittyy nykymaailmassa. Joko ymmärretään, että valtiot eivät ole yksikielisiä, vaikka niin usein ajateltiin kansallisvaltioiden muodostumisen aikana? Syntyykö jännitteitä monikielisten suurkaupunkien ja maaseudun välille? Toivon ainakin, että kestävän monikielisyyden arvo yksilöille ja yhteisöille ymmärretään myös 2020-luvulla.

***

Kalle Korhonen on Koneen Säätiön tiedejohtaja, joka oli vastuussa myös säätiön kieliohjelmasta (2012–2016). Hänen taustansa on antiikintutkimuksessa, ja hän on klassisen filologian dosentti Helsingin yliopistossa.

Kalle Korhonen on Koneen Säätiön tiedejohtaja, joka oli vastuussa myös säätiön kieliohjelmasta (2012–2016). Hänen taustansa on antiikintutkimuksessa, ja hän on klassisen filologian dosentti Helsingin yliopistossa.

[In English below]

Suomalainen yhteiskunta monimuotoistuu ja samalla monikielistyy koko ajan, varsin nopealla tahdilla.

Varsinkin pääkaupunkisedulla muualta tulleita, muita kuin suomea tai ruotsia äidinkielenään puhuvia on jo liki 20% väestöstä, joissakin Itä-Helsingin kouluissa jo reippaasti yli puolet kaikista oppilaista. Eilen, istuessani bussissa matkalla harrastukseeni, edessäni istuva mies puhui kaverilleen somalia, takana istuvat naiset keskenään venäjää ja vieressä istuva nuori nainen puhelimeen englantia. Tämä on arkipäivää ja tulevaisuuden kuva.

Monikielisyys tarkoittaa myös paljon muuta kuin ympäriltä kuuluvaa puhetta. Suomen peruskouluissa muualta tulleille, muun kuin suomen-, ruotsin- tai saamenkielisille oppilaille, tarjotaan mahdollisuutta oman äidinkielen opiskeluun kahtena tuntina viikossa. Tätä opetusta tarjotaan valtakunnallisesti ainakin 60 eri kielessä. Kyseessä on loistava mahdollisuus, jos sen merkitys vain ymmärretään ja mahdollisuutta käytetään hyväksi.

Oma kieli, äidinkieli, on sydämen, tunteiden, identiteetin ja ajattelun kieli. Kieli vahvistaa kulttuurista identiteettiä, oman kulttuurin tuntemusta ja siteitä omaan kieliyhteisöön ja entiseen kotimaahan. Äidinkieli on myös jokaisen perusoikeus: kaikilla Suomessa asuvilla ihmisillä on oikeus kehittää ja ylläpitää omaa äidinkieltään.

Äidinkieli on se kieli, joka opitaan ensin ja johon samaistutaan. Kaksi- tai monikielisellä on itsellään oikeus määritellä äidinkielensä, ja niitä voi olla yksi tai useampia. Suomen väestörekisteri ei kuitenkaan tue tätä. Syntyvän tai Suomeen muuttavan lapsen äidinkieliä voi rekisteriin merkitä vain yhden ja tämä määrittää kielivalintoja myös koulussa. Toki nykyään äidinkielen voi helposti muuttaa tai lisätä äidinkielen lisäksi toisen kielen asiointikieleksi.

Kieli on tärkeä sekä oman minuuden tiedostamisen että kieltä puhuvaan yhteisöön liittymisen kannalta. On tärkeää, että lapsi oppii äidinkielensä riittävän hyvin, sillä äidinkieli on perusta lapsen ajattelulle ja tunne-elämän tasapainoiselle kehitykselle. Äidinkieli on myös tärkeä väline sekä uusien kielten että kaiken muunkin tiedon oppimiseen ja omaksumiseen. Oman äidinkielen vahva hallinta tukee näin myös muiden aineiden opiskelua.

Olen toiminut viimeisten vuosien aikana uudessa yhdistyksessä, nimeltä Oman äidinkielen opettajat ry. Yhdistys ajaa nimenomaisesti oman äidinkielen opettajien ja opetuksen asemaa, missä onkin vielä todella paljon kehittämistä. Haluaisin kuitenkin peräänkuuluttaa myös vanhempiin kohdistuvaa työtä. Vieraskielisten vanhempien informoiminen oman äidinkielen opiskelun mahdollisuuksista on liian usein edelleen varsin sattumanvaraista: opiskelumahdollisuuksien lisäksi vanhemmat tarvitsevat informaatiota siitä, mikä merkitys oman äidinkielen, joka usein on myös kotona puhuttu kieli, kunnollisella osaamisella on kaiken oppimisen taustalla.

Opetushallitus toteaa sivuillaan: Vastuu lasten oman äidinkielen tai omien äidinkielien ja kulttuurin säilyttämisestä ja kehittämisestä on ensisijaisesti perheellä. Vastuuta ei kuitenkaan voida asettaa, jos ei varmisteta sitä, että vastuun kantamiseen on riittävä tieto.

Oli äidinkieli tai sen määrittely mikä hyvänsä, olennaista on se, että useampien kielten osaamisen merkitys kasvaa koko ajan. Tulevaisuuden työnteko, varsinkin asiantuntijatyössä, perustuu siihen oletukseen, että tekijä hallitsee useamman kielen, vähintäänkin ymmärrystasolla. Tällöin on hyvä ymmärtää, että kieli on voimavara niin kielen käyttäjälle kuin ympäröivälle yhteiskunnalle.

Suomen kielivaranto ei ole koskaan ollut niin laaja kuin nyt. Tätä olemassa olevaa kielten monipuolista kirjoa ei pidä hukata vaan eri kielten osaajien merkitys on tunnustettava. Yhteiskunnallisesta näkökulmasta katsoen monipuolinen kielten osaaminen ja olemassaolo on rikkaus, joka pitää osata hyödyntää koko kansakunnan parhaaksi. Tällöin monikielisyydestä todellakin kasvaa mahdollisuus.

MULTILINGUALISM – opportunity from a threat?

Finnish society is becoming more diverse and, at the same time, multilingual at a very rapid pace.

In the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, in particular, nearly 20% of the population speak a language other than Finnish or Swedish as their native language and, in some schools in Eastern Helsinki, so do well over half of the pupils. Yesterday, as I was sitting on the bus on my way to my hobby, the man sitting in front of me was speaking to his friend in Somali, the women sitting behind me were speaking to each other in Russian, and the young woman sitting next to me was talking on the phone in English. This is commonplace, and a vision for the future.

Multilingualism also means much more than the speech you hear around you. Finnish comprehensive school offers pupils from other countries, whose native language is not Finnish, Swedish or Sami, the opportunity to study their own native language for two hours a week. These lessons are offered nationwide in at least 60 different languages. It is a great opportunity, if only people understand its importance and exploit it.

One’s own language, mother tongue, is the language of the heart, emotions, identity and thought. Language strengthens cultural identity, knowledge of one’s own culture and bonds with one’s own language community and former home country. Native language is also a fundamental right of everyone: all people living in Finland have the right to improve and maintain their native language.

Native language is the language that is learned first and identified with. A bilingual or multilingual person has the right to define his or her native language and may have one or more of them. However, the Population Register Centre of Finland does not support this. Only one native language can be entered in the register for a child born or moving to Finland, and this also determines language options in school. Of course, nowadays, one can easily change or add a second language as an alternative service language alongside the native language.

Language is important both in terms of awareness of self and in terms of joining a community that speaks the language. It is important that a child learns his or her native language well enough, as the native language forms the foundation for the child’s thinking and for balanced emotional development. The native language is also an important tool for learning and acquiring new languages and all other information. A good mastery of one’s native language also supports the learning of other subjects.

In recent years, I have worked for a new association called Oman äidinkielen opettajat ry (Association for teachers of native languages). The association advocates the status of teachers and teaching of native languages, which still has a lot of room for improvement. However, I would also like to call for work on parents. All too often, informing parents of the possibilities of studying their native language is still rather inconsistent: in addition to learning opportunities, parents need information about the importance of proper knowledge of their native language, which is often also the language spoken at home, as a basis for all learning.

The Finnish National Agency for Education states on its website: Responsibility for preserving and developing children’s native language(s) and culture rests primarily with the family. However, responsibility cannot be imposed if it is not ensured that sufficient information is available to bear the responsibility.

Whatever the native language or its definition, the essential thing is that the knowledge of the importance of knowing more languages is increasing all the time. Future work, especially in the field of expert work, is based on the assumption that employees know or at least understand several languages. A such, it is good to understand that language is a resource both for its user and for the surrounding society.

Finland’s language reserves have never been as extensive as they are now. This existing diverse spectrum of languages must not be lost; instead, the importance of people who know different languages must be recognised. From a social perspective, the diverse knowledge and existence of languages is a wealth that must be exploited for the good of the whole nation. This will really help multilingualism become an opportunity.

***

Riitta Salin on toiminut pitkään monikulttuurisuussektorilla, niin monikulttuurijärjestöjen kuin oman äidinkielen opetuksen parissa.

Riitta Salin on toiminut pitkään monikulttuurisuussektorilla, niin monikulttuurijärjestöjen kuin oman äidinkielen opetuksen parissa.

Riitta Salin has long been involved in the multicultural sector, both in multicultural organisations and in the teaching of her own native language.

“The Romani language is an Indo-European language, of the Indo-Iranian branch’s Indo-Aryan subset. It is a daughter to Sanskrit and sister to Hindi, Maratha and Urdu. European Romani dialects are divided into 4 main groups: the northern dialects, the Balkan dialects, the Valakian and the central dialects. The Romani spoken in Finland is a northern dialect, of its northwestern group whose historical center is in the German area.”

–Kimmo Granqvist, a., Kotimaisten kielten keskus

The research tradition of the Romani language started as early as the 1700s, when it was noted that Romani was one of the Indian languages which wandering groups of people originating in India spoke outside of India.

Research into the Romani history and culture started at the same time. And it is true that as people with oral culture and wandering lifestyle, our history would seem much shorter and more vague, if there had not been research into it from the authorities and a little bit from ourselves, too. Now we know that we are the largest minority in Europe, about 10-12 million people who have lived in Europe for 800 years or so, but information about us is still scarce. As individuals we are not interesting, as a group we are a problem – a black spot; poor and marginalized people, out of reach from civilization, human rights and equality. It is an awkward position and climbing out from there is difficult because it makes us victims and casts blame on others, whether we want that or not.

As a mother tongue, about 4 million people speak Romani in Europe, for others, the language has disappeared either totally or it remains as a household language or just a slang-like vestige of phrases and words.

Despite all our hardships and misery, we have always had something of interest, and that is our language. Interest in the Romani language just keeps growing. Today there are linguists, universities and large projects involved in the research. Top scientists, highly educated and knowledgeable people all over Europe, and the project costs are in the millions. As a mother tongue, about 4 million people speak Romani in Europe, for others, the language has disappeared either totally or it remains as a household language or just a slang-like vestige of phrases and words.